美东时间2025年3月29日晚8时,美西时间3月29日下午5时,北京时间3月30日上午9时,来自美国和中国十几所知名高校的专家学者在线上齐聚一堂,共同参加由美国中美后现代发展研究院主办的过程哲学视域下的语言学研究暨鲁枢元教授语言学思想国际研讨会。美国印第安纳州戈申大学教授贾斯廷·海因泽克在发言中说,鲁教授的理论打破了系统性与真实性的对立。语言实为三位一体,“在次语言、常语言、超语言之间其实并不存在一条截然相隔的界线,那只是一种浸润性、渗透性的过渡。”

以下是贾斯廷·海因泽克教授发言全文,马伊林、杨婧妮译:

鲁枢元教授生态政治中的三元语言

贾斯廷·海因泽克

诸位好,我此刻身处美国中西部印第安纳州的戈申镇,毗邻芝加哥。此地已是深夜,但能参与探讨鲁枢元教授关于语言起源与功能的深刻研究,我深感荣幸。先说明一点,我并非语言学专家——我的研究领域是宗教、伦理与政治。但长期以来,我一直对语言在政治想象和环境政策中的作用颇感兴趣。回想十多年前,当“生态文明”正式被中国政府确立为国家战略目标时,我深切体会到语言的力量:它既能呈现社会理想,又能弥合后工业时代人与自然之间的裂痕。

近几周在研读鲁教授著作时,我不断联想到美国当前的政治背景——尤其是特朗普执政期间环境政策的明显倒退。值得注意的是,特朗普政府上台伊始,就开始对政府机构涉及生态议题的用语进行管控。例如,今年二月,联邦机构被要求避免使用“气候变化”、“气候危机”、“温室气体”以及“环境质量”等词汇,即便这些机构本应负责国家气候研究。在某些情况下,相关官方备忘录要求严格限制此类术语,公共网站也被强制删除相关表述,拨款申请或合同中若出现这些词汇则需作标注。据《纽约时报》统计,到目前为止,已有数百个政府网站依照白宫新指示进行了修改。

从语言学角度看,这种审查可视为语言工具化的极端形态——试图将语言丰富的表达潜力压缩为服务于单一、狭隘议程的工具。实际上,这类策略并非首次出现,特朗普政府早在2017年就采取过类似措施。可以说,这不过是政治修辞工具化传统的现代表现,正如鲁教授指出,这一传统可追溯至亚里士多德。控制语言往往是掌控社会政策和压制异见的第一步。

虽然本届政府在语言工具化上的表现尤为明显,部分选民对这种压制生态话语的举措表示默许,这是否与近十年来美国进步派政治语言工具化有关?特朗普竞选时承诺抵制“觉醒主义”和政治正确,这也是其吸引选民的部分原因。许多人认为,进步派更热衷于标榜自身对知识匮乏者的优越感,而非切实推动社会或生态进步。我们有必要自问:我们的生态语言是否也陷入了某种自满与教条,恰如环境政策中的固步自封?例如,加州在民主党执政下,本有望借助高铁项目大幅改善空气质量、降低碳排放,但这一项目在通过十二年后仍因繁琐的环境审查程序而搁浅。这种繁琐的审查虽出于善意,但长达十余年的法律纠纷和无尽的等待,最终可能导致项目流产与资金浪费。值得我们思考的是,在某些情况下,进步派的生态理念是否已演变成僵化的教条,以至于脱离了实际,变成了为理念而理念的存在。许多人似乎对进步派改善现实的能力失去信心。因此,我不禁怀疑,这是否部分因为生态思维被过于抽象或工具化,从而为特朗普管控政治话语创造了条件。

当然,两种工具化不可等同:服务于环境政策的语言工具化,即便有时和生态现实脱节,也与特朗普政府审查生态话语、蓄意破坏气候行动、打压清洁能源,尤其是太阳能和风能发展的行径存在本质差异。

事实上,政治语言完全规避工具化既不现实亦不可取。作为政治概念,生态语言需要适度抽象化。它的根本目标是作为政治实践的工具——推动广泛的社会行动,而非仅仅直触感知与情感,或仅追求对人类经验的真实再现。以气候变化领域为例,我们需要建立一套严谨的科学术语体系,这些术语不仅要有明确定义、便于量化分析,更需具备驳斥谬论的能力,使关于气候变化的错误主张边缘化。政治话语需要保持规范性与体系性,但久而久之,这种规训是否正在消解语言本身的真情实感与感染力?

这时,鲁教授提出的语言三分法框架便显得尤为重要。他在《超越语言》中指出,语言由三个既独立又关联的维度构成:次语言(裸语言)、常语言(逻辑语言)与超语言(场语言)。次语言直指人类体验的“深渊”,关乎情绪和本能;常语言体现语法规则、语言结构、修辞论证等逻辑体系;超语言则彰显语言在诗歌、艺术与宗教中超越日常经验的神韵。长期以来,语言学家往往偏重于逻辑和系统性,但鲁教授提醒我们,三者缺一不可,共同构成了语言的完整功能。

我们通常认为政治语言属于常语言范畴,若真如此,我们便陷入了前文所述的困境:环境政策话语被工具化,要么是陷入教条的科学语言,要么是高压的词汇管控,抑或是因表述松散而失去执行力。

但鲁教授的理论打破了系统性与真实性的对立。语言实为三位一体,“在次语言、常语言、超语言之间其实并不存在一条截然相隔的界线,那只是一种浸润性、渗透性的过渡。”政治语言无需在效能与真实间作取舍,而应同时融入人类经验的感性、理想愿景的超越以及务实的实践维度。三种表达方式的有机交织,方能造就既具工具性又富有情感和灵性的语言。

鉴于美国近期的局势,我期盼美国能够构建出更为丰富且具有实践效能的生态话语。过去,进步派曾善于在劳工权益、种族平等与环境正义等政策论述中融入精神与宗教的愿景。我在过往的研究中也曾主张,中国的生态文明理念应从自身深厚的精神文化传统中汲取养分以保持活力。政治语言绝不能只停留在逻辑层面,而应通过具体的经验和理想的想象与民众产生共鸣。

最后,我想引用鲁教授书中关于“语言的狂欢”这一意象。他认为,这场狂欢“注定要展现在语言革命、文学革命、思想革命乃至社会革命的启示阶段”。狂欢象征着打破陈规、激发新声,我认为当语言突破常规,往往能推动社会变革。当前,我们应将价值观念与精神内涵融入生态话语体系,从而为应对气候变化和环境修复的思考与行动注入新活力。

贾斯汀·海因泽克(Justin Heinzekehr),美国印第安纳州戈申大学教授,戈申大学制度研究与评估部主任,主要研究领域是政治哲学与环境伦理的交叉领域,主要代表作有《有机马克思主义:生态灾难与资本主义的替代选择》(中译本2015年由人民出版社出版,被列为"十二五"国家重点图书),《过程中的社会主义》和《生态文明:‘中国特色社会主义’的政治修辞》等。

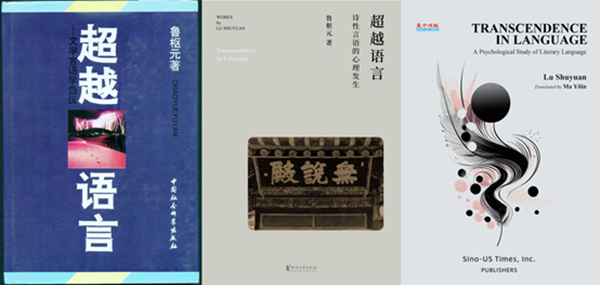

鲁枢元著:《超越语言》(初版),中国社会科学出版社1990年版

鲁枢元著:《超越语言》(修订版),浙江文艺出版社2023年版

Lu Shuyuan: TRANSCENDENCE INLANGUAGE A Psychological Study of Literary Language

Sino-US Times, Inc.1924

Lu’s Tripartite Language in Ecological Politics

Justin Heinzekehr

March 23, 2025

Greetings to you all from the Midwestern UnitedStates. I’m speaking to you from my home in Goshen, Indiana, which is close toChicago. It is late at night here, but I’m glad to be able to join you for thisdiscussion of Professor Lu’s insightful work on the origin and function oflanguage. I have to admit at the beginning that I am only an appreciativespectator of the field of linguistics – my own work is in the area of religion,ethics and politics. But I have for a long time been interested in the rolethat language plays in political imagination and environmental policy. Iremember now over a decade ago when the idea of “ecological civilization” wasofficially adopted as a national goal by the Chinese government. And that eventreally underscored for me the power that language has to present a social idealand to facilitate the healing process between humans and nature inpost-industrial society.

As I’ve had the chance to reflect on Professor Lu’sideas over the last few weeks, I’ve been thinking in terms of a differentpolitical context, namely the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election here in theUnited States, an administration that is not only dismissive but activelyhostile to environmental policies. It is interesting in the context of ourdiscussion of linguistics that one of the immediate actions of the Trumpadministration has been to try to control the language used by governmentagencies when they refer to ecological issues. In February, for example,agencies were told that they should avoid terms like “climate change,” “climatecrisis,” “greenhouse gases,” or “environmental quality,” even those agenciesthat are responsible for national climate research. In some cases, agencies arebeing ordered to limit their use of these terms in official memos, eliminatethem from public websites, or flag these terms when they see them appear ingrant proposals or contracts that are submitted to the agencies. So far,hundreds of government websites have been edited to conform with the newlanguage guidance from the White House.

In linguistic terms, we could seethe censorship of the Trump administration as an extreme version of theinstrumentalization of language – an attempt to reduce the expressive potentialof words to a mere servant of a homogenous and narrowly-defined agenda. This isby no means a new strategy, even for the Trump administration, who engaged insimilar censorship back in 2017. In fact we might see this as only the latestmanifestation of a long, and maybe even universal, tradition ofinstrumentalized political rhetoric. Or at least one that, as Professor Lu hasnoted, goes all the way back to Aristotle. Control over language has oftenbeen a first step toward control over social policy and control over potentialopponents of those policies.

Although the instrumentalizationof language during this administration has been much more obvious, I wonder ifthe censorship of ecological language has been made palatable to some voters inpart because of a parallel instrumentalization of progressive politicalrhetoric in the United States over the past decade or so. Part of what appealedto voters about Trump’s campaign was the promise to resist “wokeness” orpolitical correctness. For many in the United States, there has been a feelingthat progressive language is more concerned with signaling one’s ownsuperiority toward the less educated or the less knowledgeable than it is aboutactually working for social or ecological progress. It is worth askingourselves whether there has been a certain complacency or rigidity in ourecological language that has corresponded to a complacency in environmentalpolicy. I’m talking about the kind of complacency that might be manifested, forexample, in the failure to develop a high-speed rail system in theDemocratically-led state of California. That’s a project that could drasticallyimprove air quality and reduce the state’s carbon output, and yet 12 yearsafter the project was approved there is still no high-speed rail system. Inpart, the failure of that project is due to the complicated environmentalreview process that was put in place by progressive politicians with goodintentions. That environmental review is still ongoing after more than adecade, with lots of pending legal challenges and no end in sight, and it islikely that the rail project will ultimately be abandoned and millions ofdollars gone to waste. It is at least worth consideringwhether in some cases the progressive concept of environmentalism has become sorigid or so dogmatic that it has actually lost touch with the practical workthat needs to be done, and has actually become an end in itself. Many peopleseem to have lost faith in the ability of progressive politics to make any realimprovements in their lives. So I wonder whether it may be partly an overlyabstract or instrumentalized version of ecological thinking that has paved theway for Trump’s attack on political language.

This is certainly not to suggestthat the two forms of instrumentalization are equivalent: theinstrumentalization of ecological language in service of environmental policy,even if it’s become somewhat disconnected from ecological reality, is a verydifferent thing than the instrumentalization that the Trump administration isengaged in when it censors ecological language, purposefully undermines effortsto mitigate climate change, and actively discourages the production of cleanenergy, solar or wind power especially.

And in fact, it is not possiblenor desirable for political language to avoid instrumentalization altogether.In order to function as a political concept, ecological language requires somelevel of abstraction. Its very purpose is in fact to be politicallyinstrumental – to support practical action on a broad social scale and not onlyto be directly in touch with perception or emotion or to try to be an authenticexpression of human experience. It was necessary to develop a specificscientific vocabulary for climate change, for example, that would have strictdefinitions, that would lend itself to measurement and analysis, and even thatwould devalue and marginalize false claims about climate change. In politicaldiscourse, then, we need some level of control and system in the language weuse, but the question might be how much we end up sacrificing in terms of theauthenticity or the appeal of that language in the long term?

This is where I find Professor Lu’sthree-part framework of language very helpful. In his book Transcendence inLanguage, Lu writes that language is made up of three distinct butinterrelated modes: the sub-language or naked language, the ordinary or logicallanguage, and the super-language or field language. The first corresponds tolanguage that is most closely related to the “abyss” of human experience,direct emotion or instinct. The second relates to the logical system oflanguage, including rules of grammar, linguistic structures, rhetoric andargument. The third mode relates to language’s ability to transcend ordinaryhuman experience in realms of poetry, art and religion. Linguists have tended toprivilege the logical or the systematic form of language, but Lu shows us thatall three of these modes are essential to the holistic role of language forhuman society.

We usually think of political languageas belonging to the second category – the ordinary or logical language – and ifit was true that political language was limited to this category, we would bestuck with the dilemma I unpacking earlier. The only options for our discoursearound environmental policy would be different versions of instrumentalization,either an analytical, scientific language that eventually collapses intodogmatism and cynicism, or a domineering control over the official vocabulary,or even a weakened instrumentalism that is looser in its language but also lesseffective at driving social change.

But rather than thinking ofsystem and authenticity as mutually exclusive, Professor Lu helps us see thatlanguage is really a trichotomy where all three of its aspects – thesubconscious, the logical and the transcendent – need to be exercised, and thatthere are actually not strict boundaries between these modes, but smoothtransitions between them. Instead of thinking that we needto sacrifice effectiveness for authenticity, maybe we need our politicallanguage to include something of the immanence of human experience andsomething of the transcendence of an ideal vision alongside its practical dimension.The weaving together of these modes of expression would actually result in amore effective, more instrumental language.

Given the recent events in theUnited States, it is my hope that we find a way toward a richer ecologicallanguage that also be more practically effective. Progressive politicians inthe United States used to be more comfortable, for example, articulating aspiritual or religious vision supporting the logical and scientific argumentsfor specific policies around labor rights, racial equality and environmentaljustice. I’ve argued in some previous work that the political idea ofecological civilization in China should draw from its rich spiritual andcultural traditions in order to stay relevant and fresh. We can’t neglect thepotential for political language to move beyond the logical and to connect withpeople through concrete human experience or through the imagination of anideal.

And so in closing I want to justhighlight an idea that Professor Lu has in his book of a “carnival of language,”which, he says, “is destined to be shown in the inspiring stage of linguisticrevolution, literary revolution, ideological revolution and even socialrevolution.” A carnival is a time when therigidity of conventions are relaxed and novelty is encouraged, and I think it’sright to connect creative linguistic novelty with the possibility of socialchange. There are real opportunities now for us to do a better job invitingvalues and spirituality into the vocabulary of ecological language to refreshour thinking and action around climate change and environmental healing.

相关链接:

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会01:过程哲学视域下的语言学研究暨鲁枢元教授语言学思想国际研讨会成功举办

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会02:让诗性语言照亮充满生机的地球

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会03:一部极具现实意义的旧作

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会04:全息的、生态的、宇宙论的语言学贡献

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会05:语言与生生不息的地球

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会06:《超越语言》富有十足的创新力和前瞻性

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会07:AI生成語言視閾下回視魯樞元的《超越語言》

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会08:语言的心理维度与生态维度

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会09:从结构主义到生态主义

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会10:运用语言最终是为了超越语言

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会11:《超越语言》的学术贡献

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会12:《超越语言》的学术贡献

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会13:鲁枢元教授生态政治中的三元语言

鲁枢元语言学国际研讨会14:请给人性留下一点空间